Srikanth Pilla spends his days collaborating with some of the world’s most well-known car companies.

But the prolific researcher and automotive engineering professor didn’t actually drive until he was 21 years old — shortly after he’d left India and moved to the U.S. to pursue his master’s degree (and then his Ph.D.) in mechanical engineering. The young grad student secured his driver’s license, then his first automobile: a Honda Accord with 160,000 miles on it, which he drove until it turned the odometer to 220,000 miles.

Srikanth Pilla Image Credit: Clemson University

Decades (and many cars) later, Pilla now works closely with Honda — along with dozens of other automotive companies, helping them get more mileage from, secure safer rides for and enhance the sustainability of the products they put on the road.

Like many of his Clemson colleagues and collaborators, the Jenkins Endowed Professor of Automotive Engineering devotes himself to developing the kind of big, relevant innovations that bring about global change. He does so somewhat uniquely, though: by working at the intersection of academia and industry, collaborating with experts and young engineers alike.

Pilla’s ideas — as well as the ones he’s instilling in emerging engineers — promise to change the landscape of the automotive industry forever.

“Developing new talent and new concepts: that has been my dream,” Pilla says. “I am living my dream.”

First steps

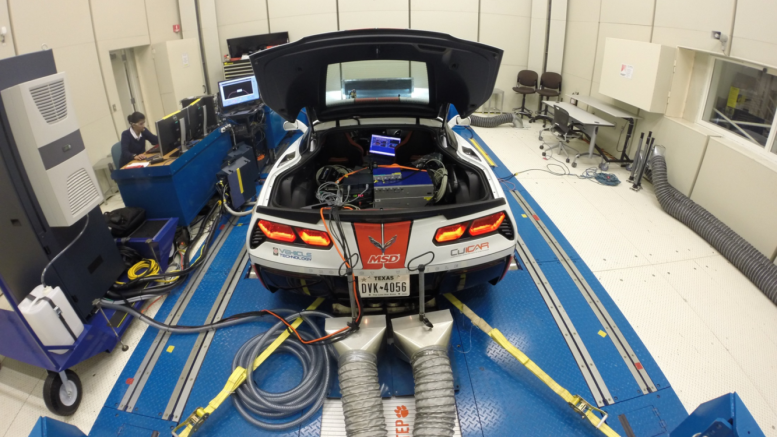

When Pilla first arrived at Clemson, the idea for a Clemson Composites Center — a one-stop-shop for academic research, design development and real-world manufacturing solutions — was already in his mind’s eye. He envisioned a place where he and his fellow researchers could create real-world applications of academic research designed to net huge gains for industry.

But bringing that vision to life, like so many novel ideas, would require years of perseverance, outreach and collaboration.

Today, Pilla is a 40-year-old father of three children, ages 1 to 10. His new Composites Center is already doing the work of streamlining vehicle-component manufacturing, such as car doors and the center consoles in high-end vehicles.

But when Pilla first proposed the idea of a composites center, he was a young, 30-something automotive engineering professor just starting at Clemson. At the time, there was nothing regionally and very little nationally or even internationally to hold up as a successful model of success for such a center.

“I said, ‘We know that it’s a high risk. But we’re willing to take that risk,’” Pilla recalls of his early conversations with various leaders in academics. Even now, Pilla says his research group is one of only a couple in the world approaching composites manufacturing in this way.

He took his first steps forward in 2013 by presenting the composites center concept to his department chair. He received encouragement but persisted with caution, leading to a larger college-level meeting with faculty from cross-disciplinary areas. Although it was “fruitful” to assemble such a large gathering of eminent scholars, he recalls, the idea didn’t progress — at least not right away.

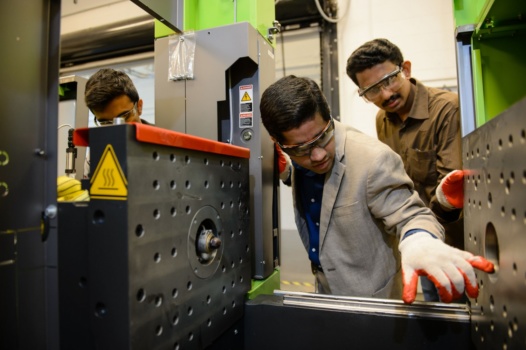

Srikanth Pilla works in his lab at the Clemson University International Center for Automotive Research (CU-ICAR).

There were starts and stops, opportunities and challenges, but advancing his vision — and the opportunity he knew it would provide to young engineering students and industry alike — never left Pilla’s horizon.

Then, in 2015, there was a breakthrough: a $5.81 million award from the Department of Energy to fund his research on creating fuel-saving, ultralightweight doors.

When the grant was submitted, even though it was not for the Composites Center specifically, it boosted confidence in the idea of such a place, Pilla recalls. Clemson was the only university to receive the DOE award at the time, which, he explains, was “a big deal.”

“Universities are known for the fundamental research, not the technology,” he explains. “But with the DOE grant, people started trusting the vision; then they started believing that this is something that can actually be done at Clemson.”

Next, Pilla worked through the University’s partnerships office to reach out to industry stakeholders and solicit their input on exactly how they would use the technology his group was advancing. He connected with people in business to talk to them about creating products that everyday people could use.

Relationship by relationship, contact by contact, he rallied support behind his ideas.

By 2017, University leadership, the South Carolina legislature and the general supply chain were behind him, academically and financially. In 2018, the University broke ground on the Clemson Composites Center. Construction wrapped up in late 2019, and the Center is scheduled to come online before the close of 2020.

“The unique infrastructure for composites,” Pilla says, “was created.”

Idea to reality

Starting with the DOE grant, every partnership and every collaboration that Pilla built moved him one step closer to the Composites Center idea he had long envisioned.

Pilla and his team of researchers fabricated a driver’s-side front-door assembly for a large original equipment manufacturer (OEM) using carbon-fiber-reinforced thermoplastic composites. They were able to reduce the door’s weight by more than 40 percent, innovating a way for automakers to improve fuel efficiency in their cars.

But the light-weighting advantages of multi-material components is something that Pilla knew would be attractive to many industries, from transportation to home appliances. The manufacturing challenge of mixing materials needed to be widely addressed.

Why? Because it requires multiple processes and multistep joining techniques, both of which drive up costs significantly.

“Oftentimes, you see a lot of purely focusing on expanding fundamental research but not scaling them up to meet industry demand,” Pilla says. “That has been my single-point selling mantra: going out and saying we should target impacting industries.”

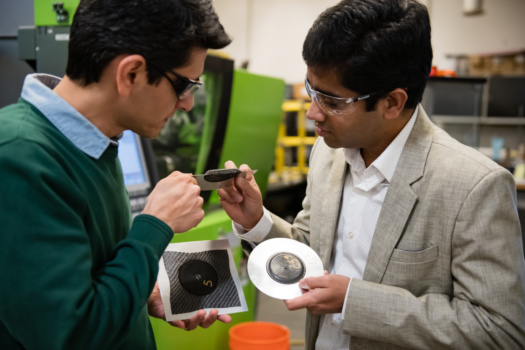

With that in mind, Pilla and a graduate student invented a solution to the mixed-materials problem. Their innovation eliminates the time and cost of multiple machines doing the work of stamping out metals on one machine, polymers and composites on another and then bonding them together in a third process.

Called hybrid single-shot manufacturing, the creation and blending of components is all done on one machine. Not only are they mistake-free, they fit snugly together and, as important, the technology can be incorporated into existing equipment. That means industry doesn’t have to make huge, up-front capital investments to enjoy the long-term economic benefits of the technology.

“It’s not just about two things happening on one machine,” Pilla says. “It’s about the cost-saving aspect of that.”

Srikanth Pilla, right, and Saeed Farahani inspect some of the parts they created as part of their research into hybrid single-shot manufacturing of metals and composites.

Centered on students

Targeting the needs of industry creates opportunities for emerging engineers, and Saeed Farahani is one of them.

The motivated grad student relocated to Greenville from Tehran Polytechnic in Iran so that he could work under Pilla as a Ph.D. student at CU-ICAR. Together, they developed the hybrid single-shot manufacturing technology.

“My academic background is in metal forming, but my experience is mostly on composites and plastic tool design. So, with this subject, I can combine these two together,” Farahani says.

Farahani secured his doctorate in automotive engineering under Pilla’s mentorship, and he is now continuing this work as a postdoctoral researcher at the Clemson Composites Center to further refine a “concept design tool” as well as “digital twin” technology, both of which are taking composites research to the next level.

By using artificial intelligence to refine the manufacturing process, researchers and industry leaders are able to learn about and refine the machine’s capabilities without the expense of costly experiments. Instead, they do this through physics-based models that help the machine understand its limitations, the researchers explain.

Next steps coming out of the Clemson Composites Center are for researchers to continue testing the new hybrid single-shot technology and other innovations like it.

The end goal is simple, even if the technology is not: making real components that industry can use.

Srikanth the boy

Growing up in India, young Srikanth would be the first in his immediate family to attend college. But he had an extended family that included several mathematicians. He recalls knowing from an early age that his mindset was less mathematical and more engineering oriented.

“I was in fourth or fifth grade, and I remember our TV was broken. My dad called a technician to come and fix it, but when he arrived, my parents weren’t home,” Pilla recalls. “He opened the back side of it and pressed a small button, and our television started working. He said the cost was $10. In the 1980s, that was a lot of money in India.”

He didn’t have the money to pay him on hand, so the technician turned the TV back off and said he would come back later if his parents still wanted it fixed.

“Once he went away, I took a screwdriver and opened up everything,” Pilla recalls. “I stood the same way he did, in the exact same position. I know he did something. I thought, ‘There was some button that had to be pressable.’ And then it clicked. I figured it out, turned on the television and it started again.”

When his parents came home from work, they asked how much the repair was going to be.

“I said, ‘zero dollars.’” He turned the TV on, and the public-access government programming they were accustomed to watching appeared on the screen. The television was in working order. Says Pilla, grinning at the memory: “That was the first thing I fixed in my home.”

Decades later, he still embraces the ideas of innate curiosity and bold work ethic in his engineering students, saying he’s more excited to promote a young researcher’s accomplishments than he is to announce a million-dollar grant.

“I always wanted to be in academia because working with students and developing students to create new technology is my passion,” Pilla says. “That’s what’s exciting. If someone offers a million-dollar research award, then I am happy, but if they offer my student a job, then I am excited, and excitement is a bigger emotion than happiness. Students do the real work, and working with them has been a big motivation.”

He recalls one young undergrad who started out with him as a volunteer researcher just out of high school and who then went on to spend four years in his lab, ultimately publishing with Pilla on more than one occasion.

“The kind of experience he got in my lab impacted him positively,” Pilla recalls. “It made his career path. When he left, he called me and said, ‘Dr. Pilla, I didn’t know where to go, what to do four years ago, but your lab helped me see the next 30 to 40 years in composites and plastics.’

“He’s 21 or 22 years old, and he’s going to spend his life doing something that he learned in my lab.”

Be the first to comment on "Clemson University; A driving force of industry-shifting innovations"