“A sleeping pill for night squawks.”

The campy slogan in the magazine ad belied the danger of a prescription drug called Doriden. Introduced in the 1950s, it was touted as a safe alternative to barbiturates. It would turn out to be about as safe as a long-tailed cat in a room full of rocking chairs.

Classified as a “hypnotic sedative,” it would prove to be even more dangerous and addictive than the drugs it sought to replace, with devastating withdrawal and rebound symptoms like hallucinations, delirium, and convulsions. It was so potent, particularly when combined with a common pain reliever of the day, that it would, according to a 1982 New York Times article, become an “inexpensive and hazardous substitute for heroin.”

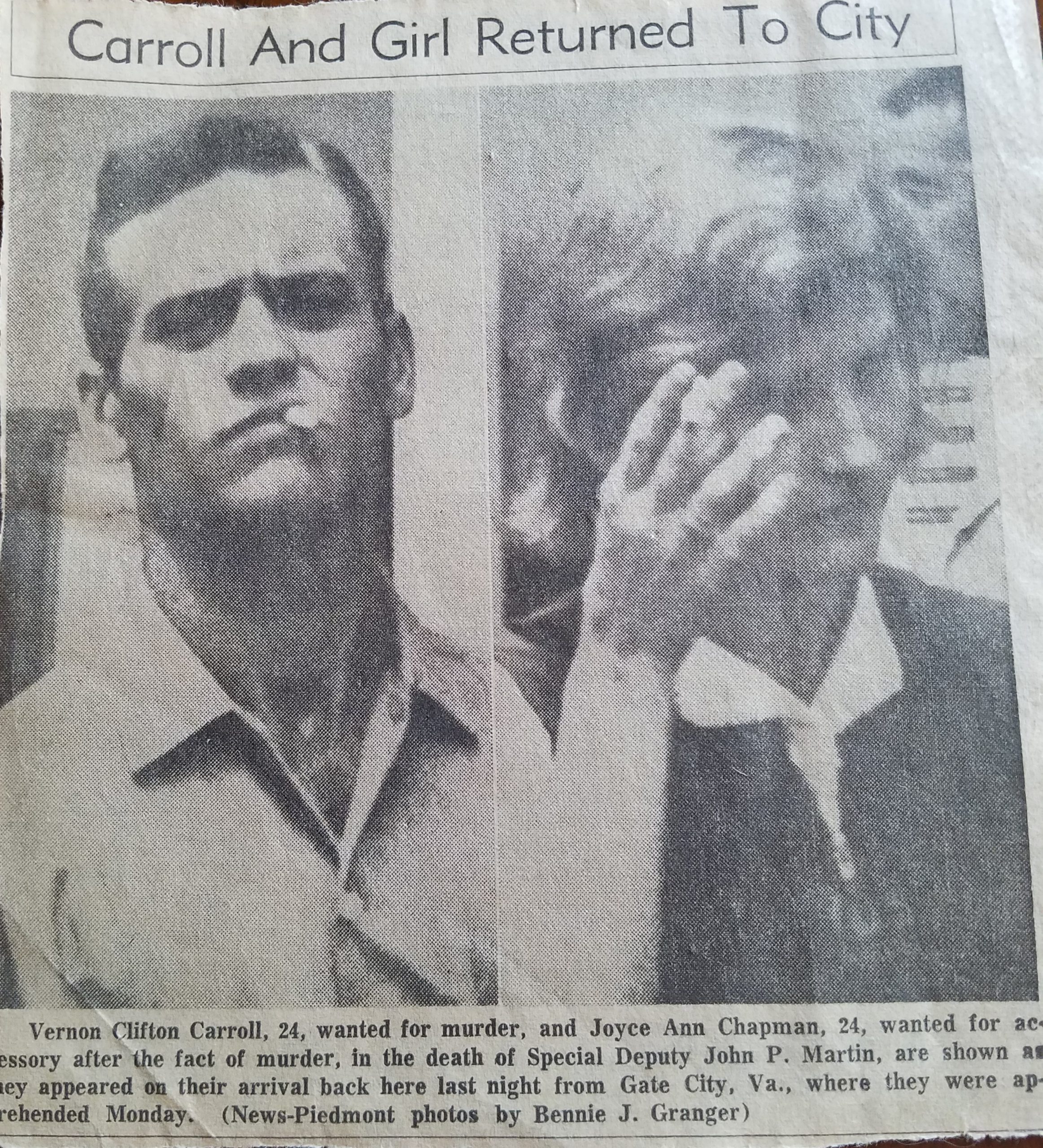

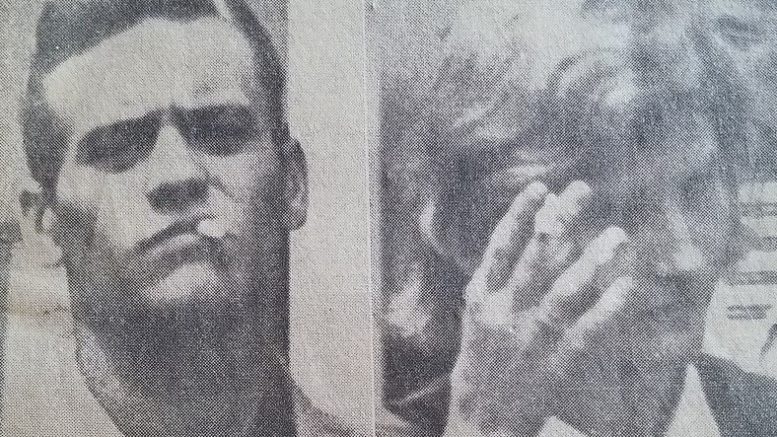

And Vernon Clifton Carroll loved the stuff.

Born in 1941 in the small coal-mining town of Appalachia, Virginia, whose only distinguishing feature is being spitting distance to Kentucky, Tennessee, and North Carolina, Vernon Clifton Carroll would learn about life’s hard knocks at an early age. His mother left the family when young Vernon was just nine months old, at which time his care was handed over to his great-grandmother. Vernon’s father, Vernon Carroll, Sr., would eventually be granted a divorce from young Vernon’s mother on grounds of desertion. While they were somewhat estranged, Vernon and his father held on to a thread of a relationship, with the elder Carroll teaching the younger about guns, and noting that as the boy grew, so, too, did his interest in firearms. Young Vernon’s formal education would end in the eighth grade.

Vernon would grow into a handsome, dark-haired young man, who found he had the preternatural ability to turn the heads and hearts of most any girl he met. An enviable talent, to be sure, but one which, when left unharnessed, resulted in an early marriage at the tender age of eighteen, to a fellow Virginian of the same age, Jacqueline Lowe, who was pregnant with his child. They would go on to have three children together, in rapid succession, but the relationship unraveled a little more every day, like a loose thread on a well-used apron.

Just five days shy of their third anniversary, Vernon walked out, leaving his wife and young children without a word of warning or a source of income. In a scene eerily reminiscent of Vernon’s own childhood, Jacqueline would file for, and receive, a divorce on grounds of desertion in 1962. Since his vocation as an automotive body shop worker didn’t tether him to any particular geography, Vernon headed down to South Carolina and settled in.

It wouldn’t be long before the Coal Country Cassanova was up to his old tricks.

Vernon was a charmer, and, some would say, a manipulator, a skill he frequently put to use on the women who had the misfortune to catch his eye. And a couple of local girls were about to find out just what kind of demons could lie behind an angel’s smile.

Peggy Lee McCombs was a small town girl, born and raised in Marietta, SC in Greenville County. She was a pretty girl, slender with chestnut hair, known to be quiet and easygoing. For a man like Vernon, who knew his powers and lacked any compunction about using them, Peggy was a perfect target. The two met while working the same shift at Gayley Mill in Marietta, a “modern” facility at the time, boasting air-conditioning; one of the jewels in the Milliken textile family’s crown when it was built. It wasn’t long until they were seeing one another, and, after a whirlwind courtship, married in 1964.

The marriage was a disaster from the start. Vernon was abusive, both physically and verbally, but Peggy stuck by his side, continuing to work to support their family when Vernon’s addiction to Doriden and alcohol rendered him unable, or unwilling, to do so. The abuse continued, and Peggy fell into the paralyzing mindset of the abused woman, both loving and fearing her unpredictable husband, and convincing herself that if she just tried hard enough, she could “fix” him.

At some point in their marriage, Vernon met Joyce.

Joyce Richards was a lovely but fiery petite redhead who lived nearby. Her father, Walter, affectionately known as “Red” for his own ginger-colored hair, was an employee at Union Bleachery, where he operated the dye kettles, and her father and mother doted on Joyce and her siblings. They were what you might call an ideal Southern family.

At least on the surface.

But as she got older, Joyce found herself frequently in trouble, and seemed to gravitate towards others who did the same.

Joyce had married Norman Chapman in 1963, a native Greenvillian of “good stock” and a prominent family. Unfortunately, her husband shared many of Vernon’s less-than-desirable traits, and was known to be a hot-head with a track record of violent physical encounters, including brawls with local gangs. As folks would say, she had “a type.”

Norman’s father had been a Purple Heart recipient in WW2, where he was killed in Anzio, Italy, the day before young Norman’s 1st birthday. Maybe it was that lingering burden of family military legacy, or maybe just to satisfy his gnawing need for destruction that led to the decision, but whatever the reason, Norman enlisted and volunteered for two tours in Vietnam. Joyce and Norman did manage, in the interim between his tours, to conceive a child, but not even that blessed event could make the marriage a happy one.

And while Norman was in the jungle, Joyce was on the prowl.

And so, a love triangle right out of a Tennessee Williams play grew between this unlikely cast of characters. Peggy was aware of her husband’s infidelity, but did not pressure him to end it. Joyce was aware of her lover’s wife and family, but seemed utterly unfazed by it. The two women provided Vernon with love, money, pills, and booze. When Vernon was no longer able to acquire Doriden on his own, it became the duty of the women to secure the pills for him. He spent most of his time in a state of semi-consciousness, unable to hold a job for longer than a few weeks, and still prone to violent outbursts, with both women becoming targets of his abuse.

Not surprisingly, this mix of drugs, alcohol, violence, and small town living would end in tragedy.

Trouble at the Sandpit

A sandpit in the middle of nowhere may not seem like an ideal gathering spot to most people, but for the ne’er-do-wells, vagrants, drug users and alcohol abusers of the northern Greenville area, it was a perfect sanctuary for their hedonism. Removed from almost any vestige of civilization, the sandpit on Freeman’s Bridge Rd between Marietta and Pumpkintown became the preferred landing place for society’s fringe elements, including Vernon and his women.

It was there that they would gather, booze it up, pop some pills, maybe get in a little target practice, all without much worry of law enforcement paying a call. Usually, no one got hurt, save the damage to their livers, brain cells, and productivity. Usually, those nights ended up in hangovers and hurt feelings from the various substances they used to escape from the world, however temporarily.

But usually isn’t always, and on the night of September 12, 1965, the regular hangout spot for Vernon, Peggy, and Joyce became a scene of brutality and violence, and that desolate sandpit would become a death trap for an innocent man.

Deputy John P. Martin

That night, Vernon was at it again. Doped up, high as a kite on God knows what from God knows who. He had talked his wife into leaving their small child with her mother and joining him and some other locals at the sandpit. Peggy was a good girl, but no angel, and she had some drinks as the night fell into the usual hazy tedium that always settled over the place on such evenings.

Just after midnight, Vernon’s drug-addled brain hatched a plan. He told his wife to go into Marietta and fetch Deputy John P. Martin, who Vernon knew usually worked the graveyard shift. Make up a story, he told her, but get him to come back to the sandpit. When Peggy asked him why, Vernon had a simple answer. He wanted the officer’s gun and badge.

One can only imagine the compromised mental state that would make a woman fear her own husband’s retribution more than the consequence of luring a lawman to a dangerous ambush. But, in the end, Peggy Lee Carroll did as her husband asked. She always did.

When she got in to town, however, she found Deputy John Martin was accompanied by Magistrate’s Constable Joe Matthews, and decided it was too risky to bring back the both of them. So she returned to the sandpit, where an incensed Vernon demanded she go back and try again. Which she did, this time with Vernon accompanying her so there would be no mistakes, no excuses. He lay low in the car as Peggy spoke to Deputy Martin, in order to remain unobserved.

As luck would have it, Deputy Martin was now alone, and Peggy told him someone had been throwing rocks at her car down at the sandpit, and asked him to follow her back. He readily agreed, always eager to be of assistance. But John Martin had no way of knowing he was about to walk right into the trap of a madman.

–

About the Author: Shauna is an Upstate SC native and graduate of Converse College and ETSU. With a passion for both history and writing (and an advanced degree in Appalachian Studies that her parents SWORE she would never use,) she is excited to be able to share stories of the colorful people and places of the South. In her spare time, she enjoys archery, rollerblading, and looking for that next great story.

About the Author: Shauna is an Upstate SC native and graduate of Converse College and ETSU. With a passion for both history and writing (and an advanced degree in Appalachian Studies that her parents SWORE she would never use,) she is excited to be able to share stories of the colorful people and places of the South. In her spare time, she enjoys archery, rollerblading, and looking for that next great story.

Be the first to comment on "Murder in Muscadine Season: A forgotten tale of love and betrayal in Greenville County (Part 2)"